Renewables have changed the world

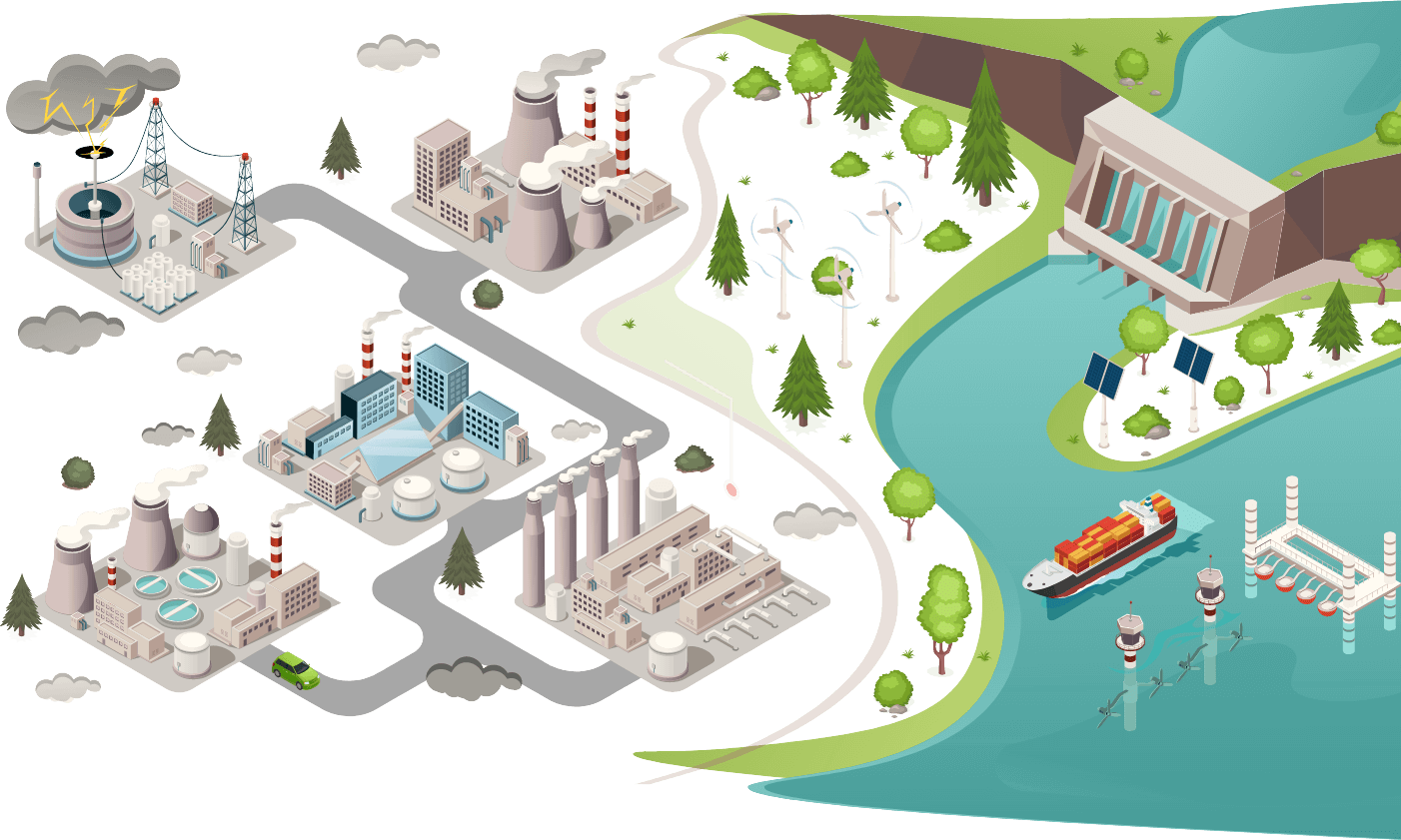

We are used to thinking of energy in discrete categories of supply and consumption. Liquids derived from oils drive transport. Gas heats homes and buildings. And electricity generated from fossil fuels, nuclear or more recently renewables, powers much of the rest.

The future will have to look very different with all energy ultimately coming from renewable energy sources—solar, wind, possibly nuclear, and with hydrogen as a complementary means for energy storage and distribution.

First, electricity generated from renewables will replace fossil fuel generated electricity. Then electricity will gradually replace other power sources in more and more applications, as we are already seeing with the rise of electric cars.

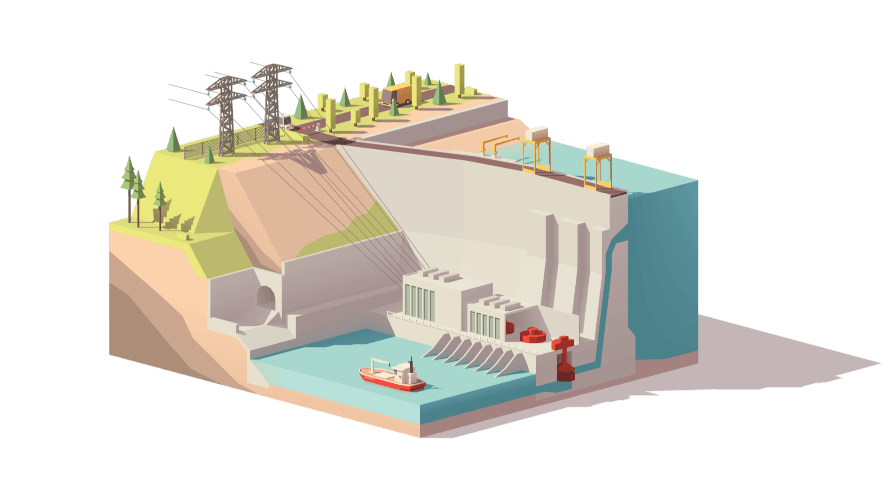

Moving this electricity around the world is where hydrogen will come in. It will be generated from solar energy in the Sahara, for example, then moved by pipeline from North Africa to Europe, or in Australia before it is shipped to Japan. Once in those countries it can be used to generate electricity in power stations, as well as being put to other end uses as a transport fuel or industrial feedstock.

SAHARA

NORTH AFRICA

AUSTRALIA

JAPAN

It is this systemic role for hydrogen, in essentially being the vehicle through which renewable energy can be moved, that means this time is fundamentally different for hydrogen. Thirty, 40 or even 70 years ago, it was imagined that the fuel could be employed for specific end uses—to power an aeroplane, for example. That meant hydrogen had to compete with any number of alternatives, often more established and cheaper. It was a steep road to climb.

Now, those specific end uses are the lowest in terms of importance for hydrogen consumption. It is first and foremost the enabler of a renewable energy revolution, which is now inevitable.

THE FUTURE IS GREEN

A few decades ago, renewable energy experts only pitched hydrogen as a fossil fuel alternative for transport. Today, carbon-neutral dreamers believe it’s the glue that holds the green revolution together and it has the potential to deliver critical functions for a new energy world.

Governments are acting

This is not simply wishful thinking. More than 30 governments across the world are considering commitments not simply to reduce emissions, but bring them to net zero. The UK and France have legally committed to do so by 2050, with Sweden by 2045, while Australia and China have developed policy documents for reaching the target.

And governments have acknowledged hydrogen will have a key role to play, not only as fuel with specific end uses, but also as means of moving energy.

Globally, states have committed US$76bn to fund hydrogen projects. The largest single commitment, of US$19.45bn, is from Japan, which has a limited ability to generate renewable energy domestically. The country has instead signed an agreement to import hydrogen in large quantities from Australia. One of the world’s major energy consumers, in other words, is fully committed to shifting towards hydrogen as the means to tap into renewable energy.

The pace of change catalysed by these funding commitments is incredible. In January for the Hydrogen Council’s annual Insights report, consultancy McKinsey identified 228 large-scale hydrogen projects that had been announced worldwide by the start of the year.

By July, that number had increased to 359. That means a third of all of the world’s major hydrogen projects ever announced were made public in just the first six months of this year.

Corporates are following

Government investment will certainly not be enough on its own, but this stimulates private investment, which will in turn drive technological breakthroughs. Government backing will also mean that green hydrogen projects are built at previously unprecedented sizes, generating economies of scale and helping to push down the price of the clean fuel.

This is exactly what we witnessed in the renewable energy sector in recent decades, as investments in technology and operating at scale gradually pushed down the cost of generating electricity from solar and wind to a point where both are competitive with fossil fuels and often, in areas of abundant sunshine or wind, far cheaper.

The last wave of hydrogen technology research was in the 1990s, but without a clear market for the fuel, there was limited backing from corporations in further developments. This time is clearly different. In analysng investments by companies that are part of the Hydrogen Council, we see a clearly accelerating trend. Members expect to increase investments sixfold through 2025 and 16-fold through 2030 compared with 2019 spending.

Companies are looking to transition to hydrogen even in countries that have not adopted net zero emissions targets. Firms think globally and know they will need to meet a high environmental bar to export into markets where emissions targets are stringent.

The cost to produce hydrogen from renewable energy could fall to between $2.29 and $2.81 in 2030.

Investment is starting to lower the cost of green hydrogen production. In 2016 a report commissioned by the Australian government said the cost to produce hydrogen from renewable energy could fall to US$9.10/kg by 2030. This year a new report commissioned by the same government said the price per kilo in 2030 is likely to be between US$2.29 and US$2.81, around a quarter of what had been forecast four years previously.

There is no need to downplay the challenges of hydrogen emerging as a global fuel. The costs are daunting, the technical progress required huge. But these are problems that can be solved by innovation driven by investment.

The path is clear and governments and companies are already taking strides down it. The hurdles will be cleared, just as they have been for renewable energy over past decades.

Daryl Wilson is the executive director of the Hydrogen Council, a global CEO coalition. Mr Wilson has worked in the field of environment and sustainability for several decades, including as the CEO of Hydrogenics, a fuel cell and electrolysis technology provider, and in roles at companies including Toyota and Dofasco.